There is something truly uplifting about being in the presence of someone undergoing a wave of motivation or ingenuity. Whilst it can be cultivated, inspiration is a limited resource. It rarely arrives when you need it most, and when it does strike, it can be fleeting.

O’Keeffe, who only recently gave birth to her first child, understands all too well the frustration of inspiration’s poor time management. “Maia only naps for about 25 minutes, tops. Non-negotiable practice time doesn’t exist anymore.” And just like babies, inspiration rarely decides to stick to your schedule. It certainly doesn’t always show up during nap time, no matter your pleading.

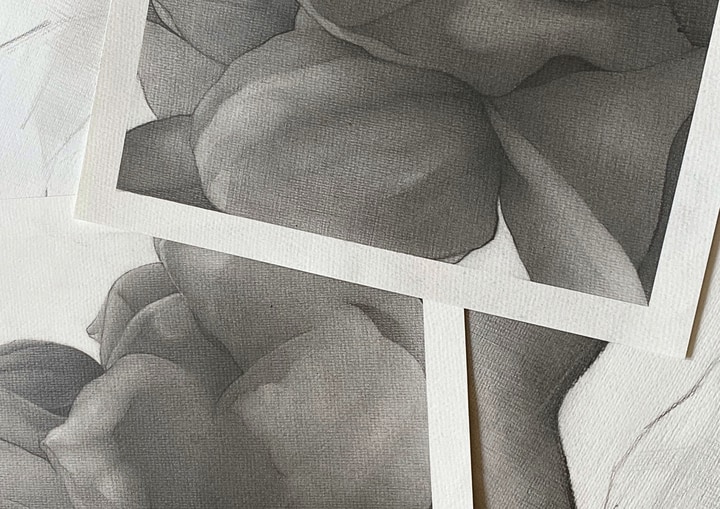

On arrival, she walks me into her sunlit living room and gestures to a large dining table where an inviting collection of new and in-progress drawings is laid out. Smooth, undulating bodies bathe in the May light streaming through the windows. Pencils and figurative art books are scattered among the display of works, hinting at her process.

Draped across textured, milk white paper are metallic, voluptuous forms. “Draped” might imply passivity, but these bodies are far from passive. There is a resoluteness to them, an assuredness in their positioning that feels assertive without being confrontational.

O’Keeffe, who is classically trained, cites Jenny Saville as an influence, something perceived in the expressive quality of her mark-making and the physicality of her forms. But unlike Saville’s often visceral, abattoir-like exposés of flesh, O’Keeffe’s voluminous figures are not bruised or smeared but coolly laid back. One might say that they are less about provocation and more about presence.

One of the first things I notice, aside from the obvious nakedness, is their quietness. Despite being so exposed, the bodies do not force shock or challenge. Quite the opposite. They are sensual but not lewd, beckoning but without constraint. If anything, they soothe and comfort; you want to be enveloped in their ease.

O’Keeffe has worked with some of the same life models for several years now. During lockdown, when in-person sessions were no longer possible, she transitioned to online drawing classes. There, she encountered women from as far afield as South America, many of whom she still draws and studies today.

When I ask why she chooses to depict larger bodies, O’Keeffe explains that her work is less about representation and more about honesty. “We don’t really know what a normal body should look like anymore. We’re bombarded by edited, photoshopped bodies on social media, billboards, and adverts. And terrifyingly, some of these bodies aren’t even real! They’re AI-generated. We’re not exposed to normal, honest bodies in the media or online world. We don’t see their edges, their grit, bumps or lines.”

As well as Saville, other art historical approaches have been a catalyst for O’Keeffe’s work; the emotional depth of Rembrandt and the unorthodox studies of Rodin, both known for their refusal to idealise the human form. Like Rodin, who captured the raw, primal nature of his subjects, and Rembrandt, whose portraits seem to hold entire lifetimes in a single glance, O’Keeffe’s figures strive to express something internal, something lived. “I am in a constant state of flux between wanting to create real, cellular representations of skin and texture alongside depicting the organic, innate, sometimes crude, experience of being human.”

For years, her biggest artistic challenge had been inviting “soul and humanity” into her compositions. O’Keeffe admits to a period when her figures felt a little flat and lifeless, even two-dimensional, something she couldn’t quite put her finger on. It wasn’t until a transformative joint residency with R.A.R.O in Barcelona and OpenBach in Paris (ending with an exhibition at Yellow Cube Gallery, Paris) that she found she was able to give her portraits a pulse. “Now I know when a work is done because it feels like it has a soul. It has a heartbeat. I want them to feel real.”

The most important thing for O’Keeffe is that these figures are not merely simulacrums but that they feel alive. “It’s not about naturalism. It’s about capturing something essential about living in a woman’s body today. The awkwardness. The strength. The softness. The tension.” Her use of dry materials, such as graphite, charcoal, and pastel, further emphasise the intimate and immediate state her work portrays.

O’Keeffe is currently working towards a new series of larger, more ambitious portraits, gesturing with an enthusiastic sweeping motion that illustrates the scale of her vision. “I want my work and these women to take up more space,” she manifests. “I want to encourage deeper conversations around self-awareness and identity, and to continue contributing to the ongoing redefinition of how we see the female body.”

These women appear to have been caught mid-moment, simply enjoying their own company. In hindsight, I realise what I felt when looking at them was a kind of longing, a yearning to feel so at home in my body that I, too, might linger in it undisturbed, draped like a silken robe and warmed by the sun.